Josef K \ Biography

For two brief years at the dawn of the 1980s Josef K provided iconic Scots indie label Postcard Records with its sharpest cutting edge. Although outlived - and outsold - by labelmates Orange Juice and Aztec Camera, Josef K perfected a prescient blend of skinny funk and leftfield pop, an artful combination of style and substance that continues to exert an influence out of all proportion to the brevity of their career.

Inspired in equal measure by British punk and American artrock bands such as Television, Pere Ubu and The Velvet Underground, Josef K came together in Edinburgh in mid-1978. Initially a three-piece called TV Art, singer Paul Haig, guitarist Malcolm Ross and drummer Ron Torrance were briefly joined by Gary McCormack, later to find fame of another kind with The Exploited. By the time David Weddell took over on bass at the beginning of 1979 the nascent group were gigging regularly, complementing a thriving local scene that also included The Associates, Fire Engines, Scars, Metropak, Visitors and Another Pretty Face.

'We were forward-looking,' recalls Malcolm Ross of this formative period. 'None of us had played in groups prior to punk so it was a clean slate. Whereas you could tell the bands who had, because they would chuck in rock guitar cliches here, there and everywhere. We never did. Paul and I were always striving to be, if not experimental, at least not clichéd. It was snobbishness to an extent. We just thought that they weren't on the same wavelength. I suppose we were quite puritanical, but modernist too. I was quite interested in the original Mod movement, and that was one of the influences in us wearing suits - from Oxfam, mind.'

Another influence, both sartorial and musical, was avant-punk quartet Subway Sect, whose landmark single Ambition appeared in October 1978. Opening for The Clash at Edinburgh Odeon, debonair TV Art duly found themselves heckled as Mod revivalists, as if aping The Jam. Fortunately sharp-eyed Johnny Waller of Kingdom Come fanzine was more perceptive. 'Take all that is best about Lou Reed, Television and The Only Ones and you come pretty close to what TV Art are like on stage.'

At this point Haig and Ross shared vocal duties, and in March 1979 recorded a promising eight song demo tape in a converted laundry, including future classics Chance Meeting and Romance. The session also featured a Fall-esque electric piano, soon to be jettisoned. 'We stopped using it because we preferred the sound of two guitars,' explains Ross, ever the purist. 'When we sold it we used the money to go and see Joy Division in London.'

'I'm not a singer and never have been,' adds Haig, confirming a shared quality - perhaps - with Ian Curtis. 'It's a croon. If it's like anything, it's like Sinatra - but not as good, of course! Billy Mackenzie was a singer, we all know know that. I'm a narrator. But I can deliver a song.'

A gig by Siouxsie and the Banshees at Clouds provided the venue for a serendipitous encounter with Steven Daly, drummer with likeminded Glasgow group Orange Juice. 'Steven arranged that Orange Juice would play their first headlining concert, with TV Art as support, at the Glasgow School of Art,' recalled OJ confederate Alan Horne. 'The method in this madness was to get Orange Juice to Edinburgh, part of Steven's arrangement including, on the following night, a performance in Edinburgh at which Orange Juice would support TV Art. As it turned out, the Art School performance justified the general belief that Glasgow was not attuned to the Orange Juice sound. Edwyn had beer thrown over him, fights broke out and the audience's behaviour was so bad that it was decided to ban groups henceforth.'

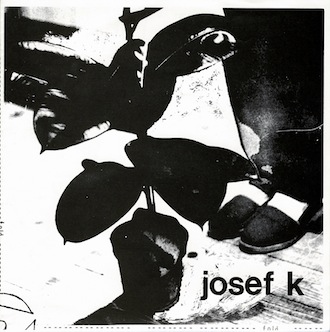

Happily both bands fared better the following night, 21 April, at Teviot Row, a student union venue attached to Edinburgh University. During the summer of 1979 TV Art became Josef K (the tormented protagonist of The Trial by Franz Kafka), and played their first show as such supporting Adam and the Ants at Clouds on 20 July. That same month a second, shorter demo was recorded with the intention of landing a deal with a credible boutique imprint such as Radar, Dindisc or Rough Trade, but failed to stir much interest. Fortunately Steven Daly decided to set up his own DIY label, Absolute, with Chance Meeting as its first - and last - release. Both sides were lifted straight from the earlier TV Art demo, and although just 1,000 copies were released in November 1979, radio airplay from John Peel finally afforded Josef K a degree of national exposure.

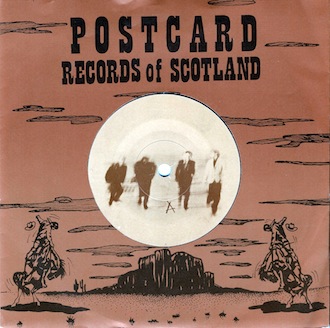

Meanwhile Orange Juice members Edwyn Collins and David McClymont, along with manager Alan Horne, borrowed money to set up Postcard Records. Arty, colourful and camp, Postcard stood in stark contrast to the drab monochrome orthodoxy of most indies of the period, though the playful presentation masked a serious intent. 'Initially Postcard was formed simply to put out Orange Juice singles,' explained Horne. 'I wanted the best band from Glasgow, obviously Orange Juice, and the best from Edinburgh, which is Josef K. Basically I just want to reach the widest possible market with their music, while keeping it totally independent of the music industry's businessmen.'

Recorded at Castle Sound in April 1980 (during a session shared with Orange Juice), the second Josef K single would be Radio Drill Time, a deft put-down of pop radio which married ringing guitar to a suitably martial beat. The flipside, Crazy To Exist, was recorded live onto 4-track to save on costs; ditto the hand-crafted wraparound sleeve, a poster-type construct which folded into four. This also doubled as the cover for Blue Boy, though through a series of mishaps - and a shortage of money - the print was delivered in plain black and white, forcing the Postcard collective to colour each and every one by hand. As a result no two examples are alike.

Felt-tipped frippery found favour with the rock press, who now ventured north in search of 'the Sound Of Young Scotland', a phrase wittily appropriated by Horne from Motown. In truth Horne was ambivalent about Josef K, and clashed with frontman Haig more than once. The Postcard supremo was also chasing Fire Engines, who had signed (inconveniently) to Fast Product. 'I still didn't like them much, but Josef K always seemed to be playing concerts at this time, on their own or supporting touring groups like The Clash, Adam and the Ants, Psychedelic Furs, Magazine, Echo and the Bunnymen and others I've forgotten. The best one I saw was at the City Hall in Glasgow with The Cure. The guitars were way up in the mix and really trebly, the audience hated them but they were brilliant.'

A growing media profile secured Josef K their first London show on 10 September 1980, opening for The Associates at the Marquee. The band ventured south again on 16 November, joining The Fall, Thompson Twins, Fire Engines and Teardrop Explodes for a jamboree at the Lyceum, but performing a largely instrumental set after Haig was stricken by flu. 'Onstage was where Josef K made most sense,' says manager Allan Campbell. 'They were now becoming formidable live performers, and Malcolm's lead playing in particular was inspiring. Fiery committed and ringing, it was a key element in the group's sound. A flirtation with psychedelic shirts and the occasional kaftan were also indicators that Josef K weren't quite the serious young men they first appeared to be - and that writers like McCullough and Morley claimed they were.'

One month later Postcard released It's Kinda Funny (Postcard 80-5), a reflective ballad which saw the band rewarded - and burdened - by hyperbolic reviews. In time, intense scrutiny and praise would come to weigh increasingly heavily on a group whose relationship with the media was never easy. 'Josef K interviews are usually a dead loss,' Campbell warned one fanzine writer, whom Ross told simply to 'write what you think, how the music makes you feel. That's what's the most important.' Soon afterwards this collective reticence saw Ross mis-identified as 'Colin' by Paul Morley in their first NME feature in October, and the quartet described (kinda funnily) as 'four shadows in search of a sunny day'.

Flush with youthful hubris and brio, Josef K even hinted at existentialist auto-destruction. Morley revealed: 'One or two albums, they reckon, and then they'll try something else. Promises...?'

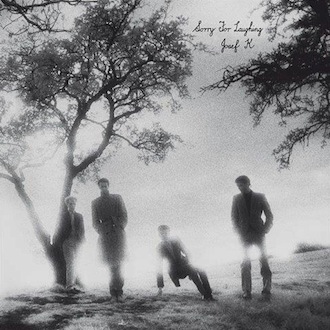

Momentum continued to build, and in November 1980 the band recorded their debut long-player, Sorry For Laughing, cutting twelve tracks at Castle Sound with engineer Calum Malcolm. Late December saw Josef K and Orange Juice cross to Brussels at the invitation of Les Disques du Crépuscule for a riotous New Year's Eve show at Plan K, a former sugar refinery. 'Five floors of magic shows, transvestites, boxing, silent films and silent freaks,' recalled Horne of this Warhol-esque happening. 'Two thousand people too, and the concert was broadcast live on the radio. We recorded a single of Sorry For Laughing and Revelation for Crépuscule before returning to London to play the ICA. The Belgian single has the sound Josef K have been looking for all along, so much so that their first studio LP has been scrapped.'

At the time no little hype surrounded the cancellation of the album scheduled as Postcard 81-1, including wild rumours that several thousand copies were consigned to the furnace. In fact only a few dozen test pressings were produced, some wrapped in unmade sleeves (featuring an exquisite solarized portrait of the band on Calton Hill by Robert Sharp), after which Horne and the band judged the set too polished and clean. 'The manic and abrasive edge apparent when we played live was missing,' explains Haig. 'We hadn't managed to capture that in the studio until the first Brussels trip.'

On 4 January 1981 Jokay and OJ were both showcased at an ICA Rock Week in London, joined by peers including Blue Orchids, Cabaret Voltaire, Dislocation Dance, Basement 5 and The Passage. 'Josef K have style,' noted Barney Hoskyns in NME. 'A scant humouring smile stays permanently on singer Paul Haig's pink lips: he picks up a guitar halfway through the set and throws in straying, sarcastic solos over Malc's intent discontent rhythm. Josef K songs are intelligently fashioned, but not inflexible: they're sexy, shrewd, smart - Magazine without the Formula or the science. So much goes on, there's so much to go on. Enlightened go-go music.'

Enlightened, yet alluringly obscure. Cerebral outsider Haig eschewed banter with live audiences, preferring instead to tape droll song introductions for playback over the PA. Moreover the band seldom played encores and declined to sign autographs. 'We never tried to make audiences like us,' admits Haig today. 'If they did, that's great, but if people didn't like us, that was fine too. I'm not sure we deliberately cultivated any kind of mystique. We just acted normally - my normal being slightly odd. I preferred using taped intros mainly because I was painfully shy and hated the sound of my speaking voice. The shyness and awkwardness certainly portrayed a sense of detachment and other-worldliness, If I'd been in the audience I would have suspected the singer was possibly an alien. We set out trying to avoid the rock cliche and in doing so might have come across as aloof and arrogant. There were usually a few raincoats in the audience, just checking us out - in a cool way of course.'

'I always think it's up to the listener what a song's about,' the singer told writer Simon Reynolds. 'I never wanted to push it down their throat. But, OK, It's Kinda Funny I wrote after Ian Curtis died. I was very upset because I loved Joy Division and was really freaked out that he could take his own life at the age of twenty-three. I thought how easy it was to disappear through the crack in the wall. It's one of the few messages I've ever tried to get through in lyrical terms. Sorry For Laughing was about how disabled people could stick together. About how they could feel they have a friendship and cameraderie that so-called able people lack. It was anti-macho. At that time I was almost anorexic - got obsessed with looking at calories and what I was eating. I was fading away to nothing at that point. And Endless Soul is about the absurdity of being alive in a godless, vacuous universe!'

When Crépuscule issued Sorry For Laughing on single in April 1981 it was widely hailed as the group's best offering to date, and established the definitive Jokay style of looping rhythms paired with incisive, angular guitar. Somewhat vexed that their strongest record yet would be released on another label, Horne pressed the band into re-recording Chance Meeting as Postcard 81-5, thus triggering a frantic burst of activity. In March several songs from the shelved debut album were given to the BBC and broadcast as a John Peel session, while the sublime Endless Soul was donated to popular NME cassette compilation C81. The following month the band returned to Europe for a string of live dates in Belgium and Holland, an excursion which also included a surreal appearance on Belgian TV, and a second stab at recording their debut album, now re-titled The Only Fun In Town.

The new version of Chance Meeting arrived in June, elevated by brass flourishes from Ross' schoolboy brother Alastair, and saw Josef K beginning to sound like a bona fide pop band. This new commercial edge was further evidenced by their one proper Peel session, also aired in June, with Heaven Sent and Missionary impressing as two fine slices of taut, crisp punk-funk, partly influenced by Brussels band Marine, who had impressed at Plan K. There were also more London showcases for Edinburgh's fast-rising stars, the first at Heaven (with Bill Nelson), followed by a support with Scars at the Venue.

Expectations for Jokay's 'debut' album now reached fever pitch, yet on release in July The Only Fun In Town drew decidedly mixed reactions. While praised lavishly in Melody Maker ('one of the few significantly original and captivating pieces of European music to find the light this year'), TOFIT was roundly slated by Sounds ('an incessant tinny racket'), with Paul Morley of NME also bemoaning 'an artificial paradise totally bungled.' Morley continued: 'Singer Paul Haig is brilliant. He acts rich as the group should do, as the production should be - but he alone cannot stop Fun being scruffy. I am appalled. Josef K have cheapened themselves and cheated the world. Not bad for a first LP.'

Barely half an hour long, and blessed with a hyper-bright production that belied six short days in an eight-track studio, TOFIT arrived as a short, sharp shock to anyone expecting Josef K to turn in the type of sophisticated pop subterfuge soon perfected by The Associates and Orange Juice. 'I think we committed commercial suicide,' rues Haig. 'When we were mixing the album we wanted it to sound like a live concert, because we were so into playing live. I purposely mixed down my own vocals. God knows why. I regret that.'

It hardly helped that The Human League were already releasing singles from Dare, the landmark electronic album which (more than any other) signaled the seismic cultural shift from post-punk to new pop. Despite being drenched in frenetic trebly reverb, however, The Only Fun In Town remains a classic genre album, with songs such as Fun n' Frenzy, Heart of Song, Revelation, The Angle, Forever Drone and the several singles sides all blessed with melody, wit and verve to spare. Sleeved in opulent black and gold, Postcard 81-7 endures as a work of dazzling pop art, as revered and revelatory as Unknown Pleasures or Entertainment, and the only album that Horne's label ever got around to releasing.

By way of promotion Josef K set out on a lengthy UK tour during July and August, with Postcard boy wonders Aztec Camera in support. The final London date, at the Venue, is preserved on the Crazy to Exist CD; the last Edinburgh show appears on Live at Valentino's. Their last hurrah was a subdued set at Glasgow Maestro's on 23 August, performed a matter of hours after the band decided to part company. Interviewed by Johnny Waller in Sounds the following year, Haig admitted to being 'pretty depressed for a week because it was the end of an era. We didn't really get on all that well towards the end. We didn't have anything in common, so there were no jokes, no happy feeling. It was just down to doing a job. Josef K weren't that famous anyway. We've split up, so what? Everybody changes.'

Somewhat fancifully, Alan Horne blamed the NME: 'The musical press caused personal differences within the group, differences I find understandable.' Critical expectation and differences over future direction certainly played a part in the premature split, but as Ross confirms: 'The main reason we split was Paul didn't want to tour. Playing gigs was how we made our living. There have been times when I wished that we'd never split up - we could have maybe stayed together and been as successful as Echo and the Bunnymen, or some other group like that. But if I think about it rationally then it's probably best that we did.'

'I've lost a lot of the ideals I had in Josef K,' Haig confided to Waller. 'About not wanting to be commercially successful, suffering for your art and all that. Not that I wasn't sincere about it at the time... But I got sick of it. I want to be signed to a major and make a great record that will get radio airplay and be a big hit. I don't mind being manipulated to a certain extent in order to get what I want, but in time I want to control everything.'

It's an ideal from which Haig, sometimes to his detriment, has never strayed. Whatever internal tensions lay behind the break-up of the band, one of the Great White Hopes of the new decade had self-destructed after just one album, thus fulfilling their own brash prophecy. Not for nothing was a later singles compilation titled Young & Stupid by the group themselves.

Older and wiser three decades on, Ross offers wisdom derived from disco. 'I read an interview with one of the guys from Chic and he said that being a musician is like being a mathematician. You're usually remembered for the first thing you did. People usually consider your early work to be the best. I know that's not true of everybody, but it is true of a lot of people. I don't lose any sleep or get frustrated about it. I'm really proud of the stuff that I did with Josef K.'

Post split, Ross' prodigious skills as a guitar slinger lead to stints in Orange Juice and Aztec Camera, and later several solo albums. Along with Torrance and Weddell, Ross also contributed to The Happy Family, who issued a highly literate pop album on 4AD in 1982, fronted by Nick Currie, later reincarnated as Momus. Paul Haig issued several excellent albums on major labels throughout the Eighties and Nineties, including Rhythm of Life, The Warp of Pure Fun and Chain, but found mainstream success elusive. To their eternal credit, the four members of Josef K have resisted all invitations to reform.

Like Postcard itself, the best band in Edinburgh might have had the lifespan of a mayfly, yet they remain a revered icon of an indie golden age. Despite having been 'appalled' by The Only Fun In Town, Paul Morley went on to commission an appropriately 'rich' cover of Sorry For Laughing for A Secret Wish, the first album by stylish German synth-pop group Propaganda, issued by ZTT in 1985. Quite what Trevor Horn would have made of Josef K is anybody's guess, though eighteen years later the producer did a fine job on Dear Catastrophe Waitress by Belle & Sebastian, whose sound and stance owes a clear debt to their Postcard forebears. Other tributes and echoes have followed (The Smiths, early James indiepop, C86, Creation, Sarah), though none more conspicuous than the astonishing chart success of Franz Ferdinand in 2004, proving once again that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. At least their label Domino partially repaid the debt by issuing a Josef K compilation, Entomology, in 2006.

More recent re-releases include Sorry For Laughing on black plastic vinyl, with The TV Art Demos as a bonus CD. 'There's so many pathways that lead to the heart,' Paul Haig wrote way back in 1980, 'the records were letters, the wrong place to start.' Three decades on, the legendary cancelled debut album by Josef K could hardly sound more right.

James Nice

With thanks to Allan Campbell, Simon Reynolds, Alan Laing, Nigel Smith

![SORRY FOR LAUGHING + THE TV ART DEMOS [LTMLP 2549]](../images/ltmlp2549.jpg)

![The Only Fun In Town [TWI 052]](images/twi052cd.jpg)

![It's Kinda Funny (The Singles) [TWI 022]](images/twi022.jpg)

![The Scottish Affair Pt. 2 [TWI 019]](images/twi019.jpg)

![CRAZY TO EXIST (LIVE) [LTMCD 2319]](../images/ltmcd2319.jpg)

![UMBRELLAS IN THE SUN [LTMDVD 2400]](../images/ltmdvd2400_330_sq.jpg)

![LES DISQUES Du Crépuscule [LTMCD 2517]](../images/ltmcd2517.jpg)